You are here

The Composer and the Poet

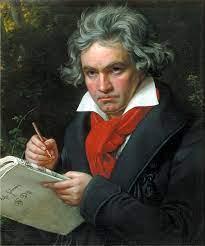

In 1809, Ludwig van Beethoven received a commission from Joseph Hartel, manager of the Court Theaters in Vienna, to compose the overture and incidental music to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s tragic play, Egmont. Hartel sought to bring plays by Goethe and Schiller to the theater, and Beethoven was only too eager for the opportunity to set a work by the leading German intellectual of the time and one of the composer’s personal heroes to music.

Beethoven also fostered a deeply held belief in the fight against tyranny, particularly in the face of the Napoleonic Wars. Bonaparte had seized control of vast sections of Europe, and after he declared himself Emperor in 1804, Beethoven famously reversed his previous esteem of the dictator and scratched his name off the dedication of the Eroica Symphony. Unfortunately, Beethoven’s symbolic gesture was not enough to end the onslaught; the French began their occupation of Vienna in May of 1809, and the composer was forced to seek refuge from the bombardment in his brother’s basement. Despite the political upheaval, or maybe inspired by it (Egmont was a 16th-century hero who led the Flemish resistance against the Spanish rule of the Netherlands), Beethoven was able to complete ten musical works for the Viennese premiere in June of 1810.

No correspondence was exchanged between the poet and the composer until 1811, when Beethoven, seeking the poet’s opinion on the work, sent Goethe the music to Egmont. An in-person encounter would not take place until 1812, when both men were staying at the fashionable spa resort of Teplitz. They spent the better part of a week in each other’s company, and while it may seem a foregone conclusion that these two titans of German culture would collaborate, or even strike up a friendship, they never met again.

Goethe would write of Beethoven after their time together, “…he unfortunately has an utterly untamed personality, not completely wrong in thinking the world detestable, but hardly making it more pleasant for himself or others by his attitude.” Conversely, Beethoven would reminisce, “How patient the great man was with me!... How happy he made me then! I would have gone to death, yes, ten times to death for Goethe.” Perhaps this disconnect is not so surprising, considering Goethe was born 21 years before Beethoven. It was a more formal age that left him respectful of nobility, entrenched in the Weimar Court, and an admirer of Mozart’s music over Beethoven’s “overblown and incomprehensible” music. By contrast, young Beethoven was disdainful of the nobility, felt that artists were the real aristocrats, and the dramatic complexity of his music was a clear departure from Mozart’s elegant simplicity.

In the end, it seems the two great artists only found common ground in their mutual admiration for Egmont and his heroism. Yet while Goethe’s play faded into obscurity, Beethoven’s overture remains firmly entrenched in the classical music canon. It was perhaps a moment of prescience when Goethe grudgingly admitted in 1814 that “Beethoven has done wonders matching music to text.” As for the composer, he maintained his sense of admiration for the elder poet; two years after the Teplitz visit, he set two of Goethe’s poems as a choral-orchestral work.