You are here

October 2023 Concert

The ESO’s 77th anniversary season opens with two of the symphonic canon’s greatest works. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Symphony No. 41, the “Jupiter,” was his final symphony, and the pinnacle of his symphonic output. A synthesis between classical and baroque eras, it is considered one of the supreme achievements of the Viennese Classical Period. Johannes Brahms’s passionate Symphony No. 2 journeys from complete serenity and melancholy to culminate in triumphal joy.

Program

Musical Insights Free Pre-Concert Preview the Friday before this concert.

Learn How to Attend!

- Mozart

- Symphony No. 41 in C Major “Jupiter”

- Brahms

- Symphony No. 2 in D Major

Pick-Staiger Concert Hall

50 Arts Circle Drive, Evanston

See map.

TICKETS

All tickets are assigned seating.

At this time, masks, vaccinations and testing are no longer required to attend ESO concerts or events. As always, we ask that if you are sick, please stay home to prevent the spread of illness. (read more detail).

Advance Sales

$42 Adult, $36 Seniors, $5.00 Full-Time Student

At the Door Sales

$47 Adult, $41 Seniors, $5.00 Full-Time Student

Children Free

Children 12 and younger are admitted absolutely FREE, but must have an assigned seat.

Please call 847.864.8804 or email tickets@evanstonsymphony.org for all orders with children’s tickets.

Composers

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

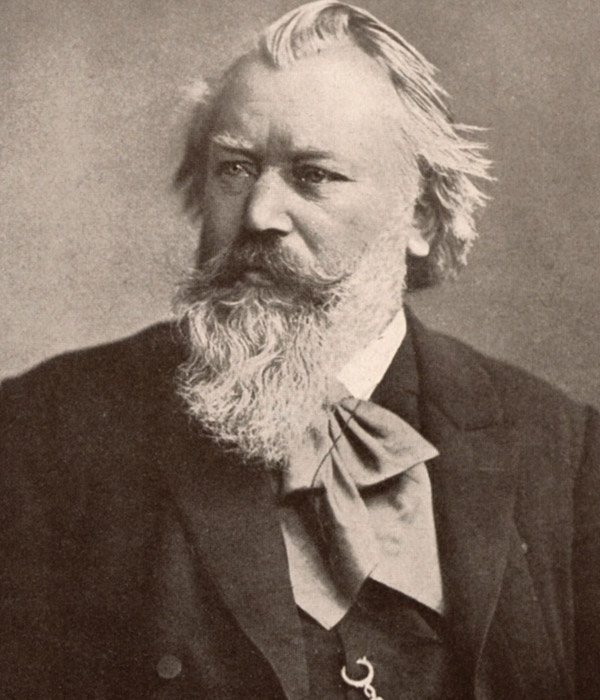

Johannes Brahms

Program Notes

Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 “Jupiter”

Wolfgang Mozart (1756–1791) 34 minutes (1788)

Ironically, it’s Mozart’s last three symphonies rather than the famous requiem that remain the mystery of his final years. Almost as soon as Mozart died, romantic myth attached itself to the unfinished pages of the requiem left scattered on his bed. The final symphonies, on the other hand—No. 39 in E-flat, the “great” G minor (No. 40), and the “Jupiter” (No. 41)—continue to beg more questions than we can answer. We no longer believe that Mozart wrote these three great symphonies for the drawer alone—that goes against everything we know of his working methods. It’s likely that the works were conceived as a trilogy, with publication in mind (symphonies often were printed in groups of three), but they weren’t published during Mozart’s lifetime.

Mozart, who didn’t expect this C major symphony to be his last, never called it the “Jupiter.” Mozart’s son Franz Xaver reported that the London impresario Johann Peter Salomon gave the work its nickname after the most powerful of the Roman gods. The nickname itself suggests that the “Jupiter” Symphony was accepted as the summit of instrumental music within a few years of its composition. Schumann, who wrote at length about many pieces he admired, thought it “wholly above discussion,” like the works of Shakespeare; Mendelssohn and Wagner both modeled youthful symphonies on it.

Salomon’s nickname probably was suggested by the majesty and nobility of the first movement, which includes the brilliant sound of trumpets and drums and features stately dotted rhythms in the opening measures (C major was the traditional key for ceremonial music in the eighteenth century).

The Andante, with muted strings to counter the noonday brilliance of the opening movement, exposes the darkness that often is at the heart of Mozart’s music. The minuet and trio are unusually rich and complicated, both musically and emotionally, for all their plain, traditional dance forms.

The finale, which includes a famous fugue at the end, is as celebrated as any single movement of eighteenth-century music. It begins innocently enough, with an innocuous do-re-fa-mi theme, and turns into a tour de force of classical counterpoint. Five themes are presented, developed, and restated; then, at the end, in the great, miraculous coda, they’re brought together in various combinations (and sometimes upside-down) in a dazzling display of perfect counterpoint. Mozart can’t have known that this work would bring his own symphonic career to an end, but he couldn’t have found a more spectacular and fitting way to crown his achievements, and, at the same time, to point the way to the future.

— Program note by Phillip Huscher, program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Reprinted with permission © Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association

Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) 45 Minutes (1877)

Within months after the long-awaited premiere of his First Symphony, Brahms produced another one. The two were as different as night and day—logically enough, since the first had taken two decades of struggle and soul-searching and the second was written over a summer holiday. This music was composed at the picture-postcard village of Pörtschach, on the Wörthersee, where Brahms had rented two tiny rooms for his summer holiday. When Brahms sent off the first movement of his new symphony to Clara Schumann, she predicted that this music would fare better with the public than the tough and stormy First, and she was right. The first performance, on December 30, 1877 was a triumph, and the third movement had to be repeated. When Brahms conducted the second performance, in Leipzig, the audience was again enthusiastic. But Brahms’s real moment of glory came late in the summer of 1878, when his new symphony was a great success in his native Hamburg.

From the opening bars of the Allegro non troppo—with their bucolic horn calls and woodwind chords—we prepare for the radiant sunlight and pure skies. And, with one soaring phrase from the first violins, Brahms’s great pastoral scene unfolds before us. Brahms knows that even a sunny day contains moments of darkness and doubt—moments when pastoral serenity threatens to turn tragic. It’s that underlying tension—even drama—that gives this music its remarkable character.

Eduard Hanslick, one of Brahms’s champions, thought the Adagio “more conspicuous for the development of the themes than for the worth of the themes themselves.” Hanslick wasn’t the first critic to be wrong—this movement has very little to do with development as we know it—although it’s unlike him to be so far off the mark when dealing with music by Brahms. Hanslick did notice that the third movement has the relaxed character of a serenade. It is, for all its initial grace and charm, a serenade of some complexity, with two frolicsome presto passages (smartly disguising the main theme) and a wealth of shifting accents.

The finale is jubilant and electrifying; the clouds seem to disappear after the hushed opening bars, and the music blazes forward, almost unchecked, to the very end. Brahms seldom mentioned his admiration for Haydn and his ineffable high spirits, but that’s who Brahms most resembles here. There is, of course, the great orchestral roar of triumph that always suggests Beethoven. But many moments are pure Brahms, like the ecstatic clarinet solo that rises above the bustle only minutes into the movement, or the warm and striding theme in the strings that immediately follows. The extraordinary brilliance of the final bar is as unbridled an outburst as any in Brahms.

— Program note by Phillip Huscher, program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Reprinted with permission © Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association